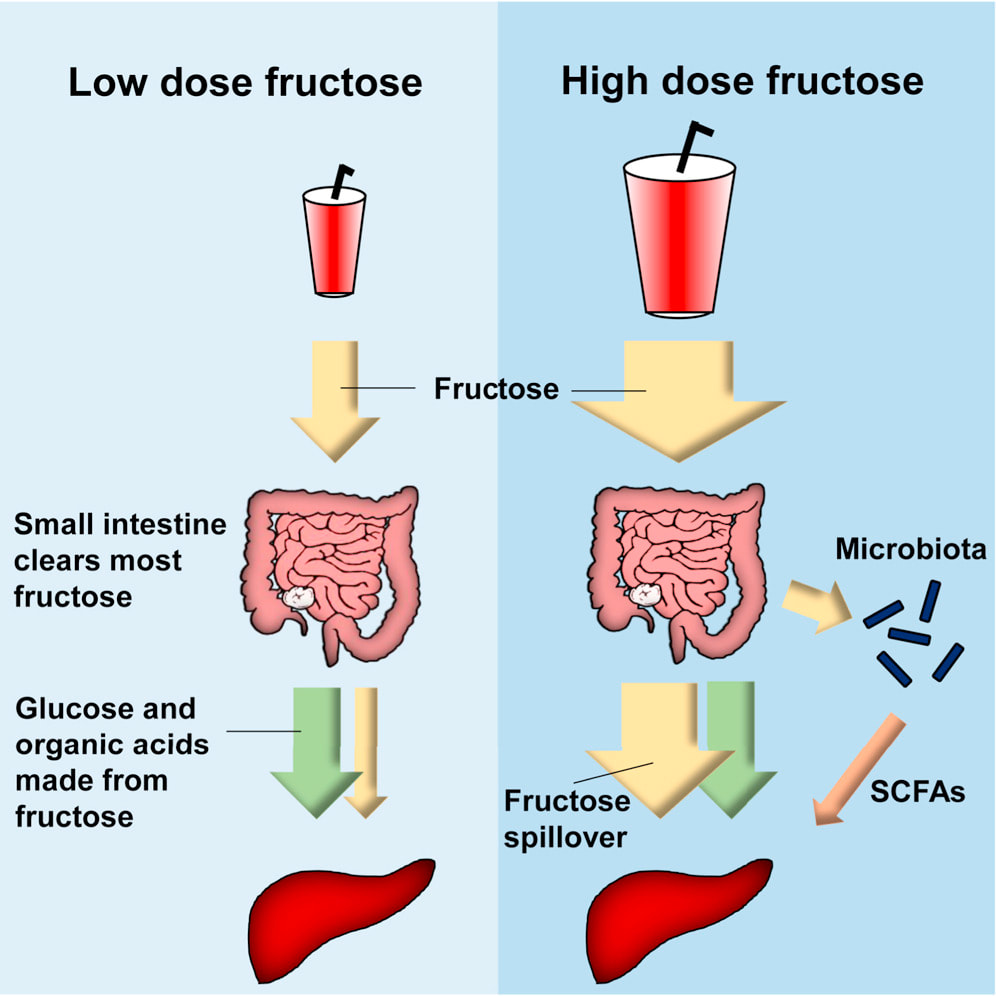

Russell Skinner, MDFructose, also called fruit sugar, was once a minor part of our diet. In the early 1900s, the average American took in about 15 grams of fructose a day (about half an ounce), most of it from eating fruits and vegetables. According Harvard Medical School, today we average four or five times that amount, almost all of it from the refined sugars (sucrose) used to make breakfast cereals, pastries, sodas, fruit drinks, and other sweet foods and beverages. Researchers point to the fact that the rise in obesity, diabetes, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in our country parallels a significant increase in dietary fructose consumption A study published in the Journal of Hepatology found that “the pathogenic mechanism underlying the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) may be associated with excessive dietary fructose consumption.” A study published in Hepatobiliary Surgery and Nutrition Journal links the increased consumption of high fructose corn syrup, primarily in the form of soft-drinks, with the development of metabolic abnormalities, insulin resistance syndrome, and NAFLD. DID YOU KNOW: Virtually unknown before 1980, NAFLD now affects up to 30% of adults in the United States and between 70% and 90% of those who are obese or who have diabetes. It is a significant risk factor for developing cirrhosis and is an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease! What is Fructose? Fructose is a sugar found in fruit. Along with glucose, fructose is one of the two major components of added sugar. It makes up 50% of table sugar (sucrose) and 55% of high-fructose corn syrup. How Fructose is Metabolized by the Body A study published in the Cell metabolism Journal found that the small intestine is the primary organ for dietary fructose metabolism. This fact was virtually unknown until most recently. The study also found that excess fructose overwhelm the small intestine and spill over into the colon and on then to the liver for processing. On its way to the colon, it comes into contact with the gut flora of the large intestine and colon (known as the gut microbiome or microbiota). Once it reaches the liver, it is turned into fat. Joshua D. Rabinowitz of the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics at Princeton University, whose laboratory led the study, explains: “The microbiome is designed to never see sugar. One can eat an infinite amount of carbohydrates, and there will be nary a molecule of glucose that enters the microbiome. But as soon as you drink the soda or juice, the microbiome is seeing an extremely powerful nutrient that it was designed to never see.” In other words, high-dose fructose saturates intestinal capacity and the extra fructose is digested by the liver and gut microbiota. Since the Standard American Diet (SAD) ultimately leads to excessive consumption of fructose, the rise in obesity, diabetes, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is no surprise. A Point of Hope Additionally, the study found a striking increase in the efficiency of intestinal fructose conversion into glucose after feeding. In other words, the ability of the small intestine to process fructose is higher after a meal rather than after a fasting state. “We can offer some reassurance — at least from these animal studies”, Rabinowitz explains, ”that fructose from moderate amounts of fruits will not reach the liver. However, the small intestine probably starts to get overwhelmed with sugar halfway through a can of soda or large glass of orange juice.” It’s good to keep in mind though that fructose, in small amounts, has been in our diet for a very long time as a species and that we usually handle small amounts very well. Of course, the amount where fructose becomes toxic and damaging varies for everybody depending on a multitude of factors, but a good rule of thumb for most healthy people is not to exceed around 50 grams of fructose per day. Check this Fructose Overload Infographic by Dr. Joseph Mercola for helpful information: Discover the fructose content of common foods, beverages, sauces, and even sugar substitutes in our infographic “Fructose Overload.”

Comments are closed.

|

Archives

October 2022

Categories

All

|

|

FOLLOW US

|

RESOURCES

|

©2020-2024 Ronit Mor LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

All statements on this website have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. The content of this website is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.

All statements on this website have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. The content of this website is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed